The Surface of a Painting, the Body of a Text: Reflections on the Works of Ruth Kestenbaum Ben-Dov

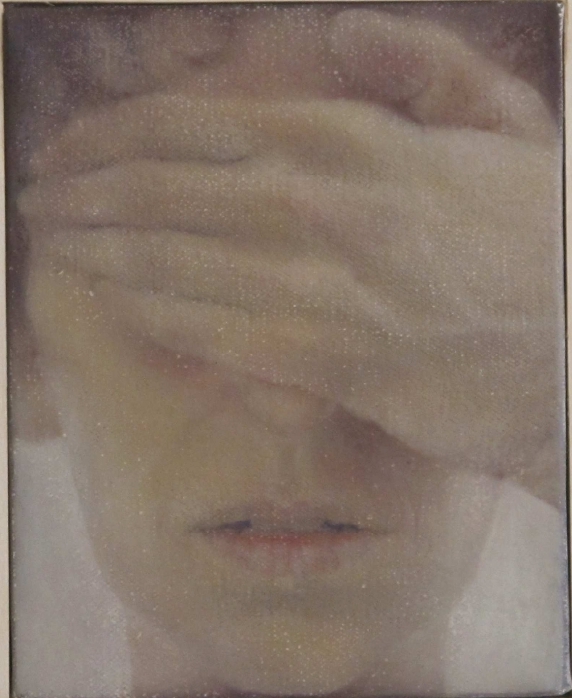

In 1998, at the Museum of Art Ein Harod, a small oil painting (19x15 cm) by Ruth Kestenbaum Ben-Dov – an artist unknown to me at the time – caught my eye. In the painting, Shema (1997, p. 10), the head of the artist is seen with her right hand palming her eyes, hiding her face, leaving only her slightly open mouth uncovered, as if captured saying the first word of the Jewish prayer "Hear O Israel" – “Shema.” Seemingly simple, this image harbors an inner contradiction also relating to the prayer that lent the work its title: we say “Hear,” not “Behold,” and cover our eyes in order not to see. Vision is conceived as inferior to audition, as obstructing or contradicting spirituality. Thus one covers one’s eyes while reciting this prayer, in utterly introspective concentration. The title Shema is associated with hearing, with the imperative and meaning embodied by the demand: “Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One.” However, painting this action involves seeing and is a product of extrospection. Kestenbaum Ben-Dov: “I paint myself not seeing – see myself not seeing.”[1] The painting examines sight and blindness, which relate to both the ceremonial act of prayer and the painting’s stylistic features.

At first sight, we deal here with figurative-realistic painting, a miniaturized fragment of a self-portrait in which the artist covers her eyes with her hand. In this respect, the painting is all about seeing and illusionist reality. However, deeper examination of the surface of the canvas reveals another aspect: the painting is grainy, its soft pastel hues blurred, visible/invisible. A screen, or semi-transparent curtain, prevents the viewer from seeing the face in all its gamut of colors. This blurring brings to mind old faded color photographs. Are we looking at a situation taking place in the present? Or are we invoking a phantom image in order to preserve and immortalize past memory? Does this screen/curtain stand to remind the viewer that this is an illusionist image rather than the “thing itself”?

In my reading, it is a bridal veil, or dreamy haze, that surrounds and covers the image. This renders it unattainable as a representation of something, which exists/not-exists for a very short moment and then fades away. This is not a face, to paraphrase René Magritte’s “This is not a pipe.”

In 1999, I curated Kestenbaum Ben-Dov’s exhibition In the Body of the Text at the Janco-Dada Museum in Ein Hod. Subsequently, I included her works in group exhibitions I curated – The Voice of Honor (1998-2000), Women Who Paint (2002), and Mystics Here and Now(2005).

The present exhibition offers an opportunity to study and present how the artist explores components of her identity while looking at her own face and faces of others who serve as her doubles, substitutes and shadows. On this occasion we can also reexamine and reread the ways in which Kestenbaum Ben-Dov investigates text/image bodies dealing with art and faith, hearing and seeing, visuality and literality, Jewish religion and culture as well as other religions and cultures.

The exhibition consists of selected works from the series Shema (1998), In the Body of the Text (1999), Welcoming Guests (2003), Prayer Rugs (2006), Remembrance (2007), and The Painter and the Hassid (2010), as well as self-portraits from various periods (1992-2011).

*

In many of Ruth Kestenbaum Ben-Dov’s works, an encounter takes place between the human body and bodies of texts. The quoted texts are taken from the Bible, the Mishna, the Talmud, and Hassidic literature. The quite realistically painted images include self-portraits, still life, Judaica, etc. The juxtaposition of bodies and words, by way of comparison or opposition, constitutes a fascinating attempt to bring together the Western painting tradition and the Jewish tradition. The works of Kestenbaum Ben-Dov provide an intimate stage for personal queries and responses and a space for reflections on the relation between religion and art, body and text and text-body and on the commonalities and differences between her religious and artistic being.

Ruth Kestenbaum Ben-Dov defines her work as “complex polyphonic painting,” and explains: “through it I try to conduct a dialogue with the world around me and with the various parts of my identity. Oil paint on canvas is analogous to the multi-layered quality of the Jewish textual tradition, in which layers of exegesis coexist on top of each other, or side by side, as on a page of Talmud. The multiplicity of meanings includes, first and foremost, the act of seeing itself, as well as questions of personal, cultural, religious and historical memory. The dialogue between Judaism and art has been present in my work for many years now. […] These two worlds are extremely demanding, they are both central to my life, while presenting me with many questions. The desire to bring them into dialogue is, therefore, a wish to be a complete human being, albeit not too complete, as I often leave the questions unanswered on the canvas.”

Her way into painting, she says, began with classical subjects such as still life, portraits and landscapes, as well as with an attempt to document the process of looking at them. As an immigrant (Kestenbaum Ben-Dov was born in the USA, and moved to Israel as a teenager), the act of observational painting linked her to the surrounding Israeli environment. However, she wanted to expand her painterly experience beyond the visible world, into invisible worlds of emotions and thoughts: “Some of the questions I have been grappling with along this journey relate to the connection between text and image: how can a painterly, visual language touch upon questions that have been discussed verbally in Jewish culture for generations? How do both these languages act upon us in diverse ways? How was the prohibition of man-made images understood over the ages, and how do I understand it? And what is the meaning of the unique tension that surrounds the representation of the human face in Jewish and other cultures? These questions have also led me to engage in intercultural dialogue with Christian and Moslem cultures.”

The tension between being and nothingness, between prohibited and permitted, and the essential, albeit contradiction-ridden, connection between the physical body and Jewish spirituality, drive the work of Kestenbaum Ben-Dov. She succeeds in creating painterly illusions that simulate reality, but at once exposes their deceptive nature and lets the viewers know that what they see is only a masterly sleight of hand: paint and canvas.

The painting Reading Faces (1998) juxtaposes the artist’s face with a Talmud page that discusses the prohibition to represent the human face: “All faces are permitted, except for a human face” (Tractate Avodah Zarah 42b). Kestenbaum Ben-Dov’s eyes are wide open, puzzled or terrified, as she peers at/reads the text. The dialogue and visual connection between them are strong, and so are those between the structure and texture of the text and the color and texture of the canvas. All these undermine the relationship of complete negation. The realistic treatment of her face challenges the text (which was written by men). The verbal language that preoccupies Jewish culture and holds a pride of place within it is both juxtaposed and opposed to the painted image.

In this and other paintings by Kestenbaum Ben-Dov, there is a cultural paradox: their subject derives from Jewish life, whereas their painterly language had developed in Christian Europe. The language of Halakhic Judaism is verbal, scriptural. The content is concrete, but the means of expression is abstract. This is in contrast to Christianity, in which, as Kestenbaum Ben-Dov sees it, spirit is viewed as superior to flesh, and the practical commandments were nullified. Nevertheless, following intense debates, painting became one of the Church’s central languages of expression; one that is in many cases is very corporeal and sensual.

The hand hiding her face in Shema and her self-portrait turning to the text in Reading Faces are but two examples of the artist’s ongoing occupation with her portrait, body and its activities during religious rituals (prayer, immersion) and during the artistic ritual (painting). Between the lines, one can sense the tension involved in her painterly treatment of the body, all the more so because the body is a female one and is always depicted within a touching distance. In most of her paintings, the body is an object of penetrating gaze. Unmarked concretely in terms of national or religious identity, the female body portrayed in the paintings has a feminine virginal, gentle and even erotic quality to it. Kestenbaum Ben-Dov depicts herself in climactic intimate moments of the religious experience.

As far as Kestenbaum Ben-Dov is concerned, dealing with the text is a “physical” activity, and the “body of the text” is likewise treated sensually and tactilely. Aware of the “art and language” tradition (from “picture-poems” of the Golden Age of Spain up to conceptual art of the 1970’s), she stresses the forms and formats of traditional bodies of texts (which were laid out differently on pages of the Bible, the Mishna, the Talmud, or in a manuscript of Rabbi Kalonymos Shapiro) turning them into figurative, physical components, just like a woman’s image.

Kestenbaum Ben-Dov tries to settle the contradictions between Jewish culture and art. The former is sometimes perceived as a realm of words and spirituality, whereas the latter is thought of as a world of pictures and materiality; Judaism is often seen as a field of restrictive laws, and art as that of liberating freedom. In addition, Kestenbaum Ben-Dov’s works deal with the contradictions of her own life as a woman in a religious-Halakhic setting and as a woman artist operating in the field of Israeli art.

*

The point of departure of her series Prayer Rugswas an ancient parokhet (Torah ark curtain) with motifs borrowed from Moslem prayer rugs, now at the collection of the Jewish Museum in New York. Underlying the series is a dialogue between two religions rooted in a strong tradition of opposition to figurative representation, as well as an encounter with the tradition of figurative painting hailing from the West. The image of the rug becomes a forum for visual discussion about dialogue in the face of inter-religious conflict, about national versus universal values, and about personal questions concerning faith and prayer.

The paintings reconstruct the general layout of the parokhet. In Prayer Rug 2 (2003), the original biblical verses were replaced with part of the prayer ‘Aleinu leshabei’akh’ [It is our duty to praise]. This choice was inspired by the fact that prostrating, a central motif of the Moslem prayer, is referenced in ‘Aleinu’: ‘We bow in worship and thank…’ The marks left by the prostrating body on the prayer rug, or the points of contact between them, are represented with paint stains. "I was interested in the physical state of the person praying – a rug serving as a basis for prostrating, and acurtain in front of which a person prays standing upright. […] I replaced the Tetragrammaton, which appears in the center of the original parokhet, with the Arabic name of God, in order to test a boundary, to confront fear, and express the idea that, after all, He – God and Allah – is one.”

In Prayer Rug 3 (2003, p. 12), the artist is seen standing, holding a paintbrush in her hand, among the columns woven into the rug. She is wearing oil paint-stained t-shirt[2] and work trousers – her typical garb as a painter, an “art laborer.” The verses “Know before whom you stand” and “Know before whom you toil” are interwoven into the painting. Kestenbaum Ben-Dov paints a prayer, or “prays” a painting, conscious of the Sisyphean demands associated with worshipping God in the Jewish religion and with the act of painting in the “religion of art.” The act of painting constitutes tefilat yachid (prayer of the individual).

In Prayer Rug 4 (2004), the frame of the parokhet becomes the window frame in her home studio overlooking the Galilee landscape. Karmiel and above it Deir El-Assad are seen in the distance. In Prayer Rug 5 (2005), the view of the landscape is transformed into a close-up of the earth, with the imprint of a figure kneeling down, in this case in order to kiss the ground rather than to pray. Around it are the words of a prayer referring to the soil – the blessing that is recited after eating fruits of the Land of Israel – in Hebrew and in Arabic translation: “…for the tree and the fruit of the tree and the produce of the field, and for the lovely and spacious land…” The words relate the land’s beauty and fertility, yet the earth portrayed in the painting is hard and dry, and the rectangular shape with the echo of a human form within it suggests a grave.

*

A painting from the Remembranceseries is based on a pair of images pointing to the same location: the Temple Mount. The first is a gray, abstract/non-abstract, square image – a bare, unfinished portion of a wall in Ruth Kestenbaum Ben-Dov’s own home. Leaving a portion of a wall un-plastered and unpainted is an ancient Jewish practice – “Zecher lachurban” (in memory of the destruction of the Temple), echoing the vow “If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, […]; if I prefer not Jerusalem above my chief joy” (Psalm 137:6).

This image represents a reality of void or an empty space waiting to be filled. In Jewish collective consciousness, the gray square represents the hope for a near rebuilding out of destruction. The second image is that of a tile depicting the Dome of the Rock, the like of which can be found on the façades of many Moslem homes. This too is an image indicating remembrance, and a sense of identity and belonging.

"Their juxtaposition led to the difficult thought that my destruction is the other's growth, and vice versa. And the concomitant question: Does one's individual or group identity need to be based on the negation of the other's? The gray square has another meaning, namely: that life is essentially imperfect, a fragmented and partial reality. This is reflected in the unfinished or incomplete painting.”

Meeting? (2007, p. 13), another painting from the series Remembrance, was made after the artist came across an illuminated Islamic manuscript. The prohibition on figurative representation notwithstanding, that manuscript depicts Mohammad’s ascent to heavenly Jerusalem, where he meets Moses. The encounter between the prophets of both religions is displayed in the middle of the painting. To their left, there are two modern prophets, the artist’s childhood heroes – Martin Luther King, Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi; and to their right, her mother and grandmother – the former smiling, the latter seems perturbed. Could such an encounter take place?

The presence of the artist’s mother and grandmother connects the historical memory of loss that forms the basis for the series with personal and familial memory. This aspect is also present in Photographic Memory (2005), which portrays the artist as a child in two views from her family album – one alone and the other in the arms of her mother.

*

In the Welcoming Guests series, Kestenbaum Ben-Dov paints portraits of other men and women. At first sight, she seems to have abandoned self-portraiture, but on closer inspection of the women she chooses to paint, it becomes clear that she is painting the “otherness” beside and within her. This is an understanding and acceptance of one’s “self” through the understanding and accepting gaze on the “other.” All her painted come from the region in which she lives, Misgav, Karmiel and the surrounding Arab villages.[3] This is an encounter of cultures and identities characterized by the generosity implied by the precept of hospitality.

*

In the series The Painter and the Hassid, Kestenbaum Ben-Dov stages an imaginary encounter with and between two creative individuals: Malva Schalek (1888-1944), a Prague-born artist, whose paintings were rediscovered between two walls in the Terezin (Theresienstadt) ghetto after World War II; and Kalonymos Kalmish Shapiro (1893-1943), a Polish-born Rabbi, whose writings from the years 1941-43 were discovered in a milk can among the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto (and later published under the title Esh Kodesh (Holy Fire).[4] Both perished in the Shoah, but their hidden works survived.

Driven by her amazement at creative people dedicated to their work even amid life- threatening adversity, Kestenbaum Ben-Dov set out to work on the series "from the point of view of an artist who struggles to create only in the face of day-to-day exhaustion and distraction. The paintings in this series attempt to touch on that extraordinary creative power and perhaps gain some understanding of it. However, the inability to really comprehend what people underwent in that time led to the use of the diptych format in many of the works; two canvasses with a border between them that also constitute one work – on the one hand, two distant planets, here and there, and on the other, the exact same world (despite a gap of about seventy years). I recognize the border between here and there, yet attempt to cross it nonetheless."

In The Painter and the Hassid 2 (2009), the artist brings together painter Malva Schalek and Hassidic Rabbi Kalonymos Shapiro. In an imaginary and impossible encounter, Malva Schalek paints the Rabbi bending over his desk writing a sermon. The event takes place in the studio of Kestenbaum Ben-Dov who offers her guests drinks and refreshments.

In another painting, He and I (2008, p. 17), the artist is portrayed as she writes something on blank paper, sharing her desk with the Rabbi who writes his thoughts. She writes with her left hand, he – with his right. “Both of us write, he with firm belief; I with doubt. Behind me is my actual landscape; behind him – flames.” In She and I 2 (2007, p. 14), the artist painted herself touching Malva Schalek’s portrait. It is unclear whether Kestenbaum Ben-Dov’s hand is drawing Schalek’s cheek or caressing it. In other paintings, the identities/portraits are blurred: the viewer cannot easily discern who is who. Kestenbaum Ben-Dov becomes a double or twin of Malva Schalek, as she tests her ability to create in the impossibly dire and extreme conditions in which her predecessor worked until she was slain.

In some paintings Rabbi Shapiro's handwriting is magnified and becomes a painting. The enlarged, and partially illegible, words resemble a seismogram. The ground motions recorded by a seismograph are analogous here to human emotions: one can feel the Rabbi’s distress at what he sees happening in front of his eyes and the moral strength he must summon in order to continue creating/writing. Kestenbaum Ben-Dov draws the words the Rabbi is writing: “Now the sorrow is so great that the world cannot contain it.” The words remain relevant to this day, and the canvas struggles to contain them.

“In his writings the Rabbi reveals his difficulty making sense of the things happening around him, while he tries to come up with a narrative that could keep his love for God intact despite His apparent indifference. These attempts lead to the idea of Batei Gavaei, the innermost chambers in which God cries in sorrow, and which humans can enter and rebuild their bond with Him. In my work [The Israelite (2008, p. 18), From the Depths (2008), Batei Gavaei (2010)] this mysterious place is the rusted, beaten and earthly vessel in which the manuscript was hidden.”

“The paintings attempt to connect worlds far apart – the worlds of the painter and the Hassid, a universalist Judaism that is open to other cultures with traditional Hassidic Judaism; and between my world and worlds that have been lost forever.”

Do I Really Want to Paint? (2009, p. 19) may serve as the (interim) concluding work of the exhibition. In its center, the artist stands in her “work attire,” holding a painter’s brush in her left hand. Works of art are painted/reproduced on both her sides, like the pillars of Solomon’s Temple, Boaz and Yakhin: prehistoric running bulls from the cave of Lascaux; a child’s doodle (her son’s?); a self-portrait by Rembrandt; a portrait drawing by Malva Schalek; and a fragment of Kalonymos Kalmish Shapiro's manuscript. These reproductions are a sort of identity card of Kestenbaum Ben-Dov, a neuroimaging of her consciousness, preferences and personality. The question “Do I really want to paint?” remains open. The answer to it might be inherent in the act itself, in the ongoing, exhausting ritualistic ceremony of creating one more painting, and then another, and another.

Prof. Haim Maor - Curator of the exhibition

[1] Citations from the artist are taken from her various unpublished writings, which are kept in her archive in Eshchar. All texts and the permission to use them in this article were given to the author on July 4, 2011.

[2] The motif of oil paint-stained blue shirt first appeared in Portrait III (1992).

[3] Hasna(2001) is an Arab woman, Rachel (2002) is a Jewish woman of Ethiopian descent, and Sigal (2002) is an Ultra-Orthodox Jewish woman.

[4] The book is a compilation of sermons delivered by Kalonymos Kalmish Shapiro, the Grand Rabbi of Piaseczno, to his disciples in the Warsaw Ghetto during the Holocaust. The author dubbed it “Torah Innovations from the Years of Fury, 5700, 5701, 5702.” The book was first published in Hebrew in Israel (1960) and some forty years later was translated into English by J. Heschy Worch and published under the title Sacred Fire: Torah from the Years of Fury, 1939-1942 (Jerusalem: J. Aronson, c.2000). In his homilies, the Rebbe sought to provide an ideational-Hassidic answer to the difficulty to justify the mysterious ways in which God works and find a meaning for suffering and martyrdom, as well as to encourage his audience and give a sense of direction to his followers.